You should probably spellcheck your prompts

03 Jan 2024TLDR: I ask GPT-3.5 to perform a commonsense question answering task, but deliberately introduce typos in key words in each question. The results show that typos generally impair GPT’s performance. In particular, accuracy tends to decrease as the complexity of the typos and the perplexity of the typoed words increase. However, accuracy improves from 88.8% to 92.0% when we first prompt GPT to correct typos in the question, then use the GPT-corrected question for the question answering prompt.

1. Typos hurt question answering performance

If you use ChatGPT much at all, you’ve probably misspelled words in your prompts and still received fine responses. LLMs are certainly robust to some degree of typos, but not completely robust: This paper from Wang et al. shows that typos degrade the helpfulness of responses from foundation models. But as far as I can tell, it remains unclear how much typos hurt LLM performance across tasks, which classes of typos most hurt LLM performance, and how LLMs handle typos in context.

I see two primary reasons why an LLM might still effectively respond to a prompt containing a typo:

- The context surrounding the typo is sufficient to interpret the text.

- The typo is in the model’s training data.

What is uncertain is to what degree LLMs can learn typo patterns the way humans do. This may be a uniquely difficult task for GPT models because of their tokenizers. Even in a typoed word, most tokens will be multiple (English) characters long. As a consequence, models may not have circuits for handling character-wise perturbations.1

As an example, consider the strings “happy” and “hapyp”. “happy” is encoded as one token in GPT-3.5, but “hapyp” is encoded as two:

"happy" -> happy

"hapyp" -> hap|yp

Try it yourself here. You can’t rearrange “hap” and “yp” to form “happy,” so GPT can’t directly learn this character transpose typo pattern.

I can’t see what is going on inside GPT when it encounters a typo, and I’m not going to attempt to answer the pattern-learning question here. But I think a good way to lay the foundations for that sort of question is by tracking how model performance changes as we make the target word less likely and the typos applied to it more severe.

1.1. Dataset

In this experiment, I focus on single-word typos in CommonsenseQA questions. CommonsenseQA is a question answering benchmark task that tests for commonsense reasoning. I didn’t put too much thought into choosing the dataset. I wanted a QA task that didn’t require referencing outside text, and this benchmark checked that box.

Each example in CommonsenseQA has a question, answer, four answer choices, and “source concept word.” The source concept word relates the question to the answer choices. Understanding the source concept is often necessary for understanding the question, so the source concept word is a natural target for typo perturbations.

We first establish GPT-3.5’s baseline accuracy by testing it with typo-free questions. Next, we introduce a typo by altering the source concept within each question and then reassess GPT-3.5’s performance on the modified questions. Along with evaluating accuracy, we record two other things: the amount of contextual information the sentence offers about the word with the typo, and the complexity level of the introduced typo. To do this, we need a way to measure contextual information and typo complexity.

1.2. Approach

Contextual Information

We want to measure the probability of the unperturbed word given the rest of the sentence. To do this, we mask the typoed word, ask BERT to predict the masked word given the rest of the sentence, and record the probability BERT assigns to the unperturbed word, $P(\text{mask}=\text{word} \,|\, \text{rest of sentence}).$

Typo Complexity

A natural metric for typo complexity is the edit distance between the perturbed word and unperturbed word. But typo complexity should also account for how long a word is. A certain number of character-level changes to a short word constitutes a much larger word-level change than the same number of character-level changes to a long word. Randomly change three letters in “dog” and you get an unrecognizable word, but do the same to “incomprehensible” and you can probably put the word back together. So, we instead consider normalized edit distance, the edit distance divided by the length of the perturbed word.

There are a couple other methodological bits we need to define.

Prompting

Evaluations use five-shot prompts. Five examples to use in the prompt were randomly chosen and removed from the evaluation dataset. Here is one of the in-context examples:

User:

Q: Where does my body go after I am no longer living?

A) zombie B) bodycam C) coffin D) graveyard E) funeral

Assistant:

D) graveyard

There is also a simple system prompt: “You are a helpful assistant. Your task is to answer multiple-choice commonsense questions.”

Typo Transformation

We imagine a person typing a word character by character, with each character being an independent event with probability $p$ of being typoed. The type of typo is randomly chosen from four categories:

- Random replacement (40% probability): A random character is inserted instead of the correct character.

- Skipped character (30% probability): The current character is skipped.

- Adjacent swap (20% probability): The current character is swapped with the previous character.

- Repeated character (10% probability): The current character is typed twice.

These probabilities are mostly arbitrary, though I tried to make them realistic. There are two possible random events at each character in the target word: the first is whether or not there is a typo, and the second is, if so, which type of typo.

Model

I’m using GPT-3.5 Turbo (gpt-3.5-turbo-1106) with temperature = 0 (we’re only predicting a few tokens, so better to reduce noise and just argmax). I use GPT-3.5 instead of GPT-4 because it is cheaper.

For the test run, we iterate through 1,000 question-answer pairs and toss out all examples that the model got wrong without typos. Then we go through all of the remaining examples, apply the typo transformation at $p = 0.1,$ $p = 0.2,$ $p = 0.4,$ and $p = 0.8,$ and test again on all of the transformed examples. That is, for each question-answer example, we have four transformed examples with typos. Our final dataset consists of 2,458 evaluation examples.

1.3. Results

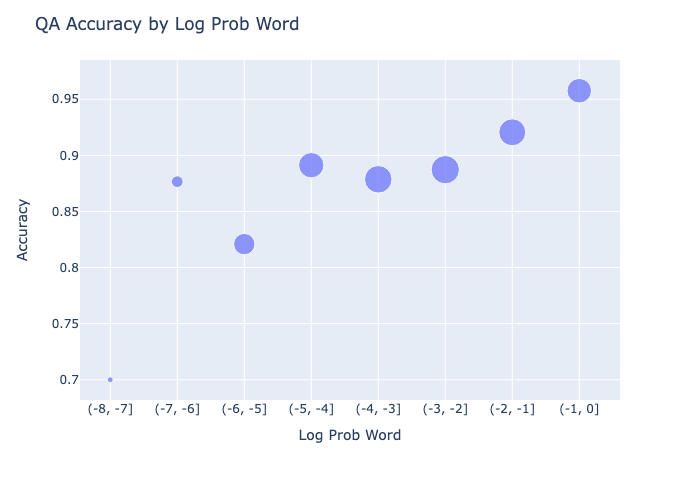

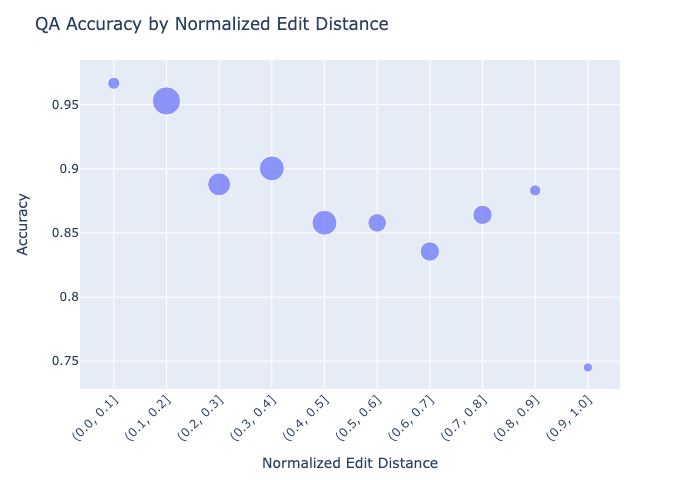

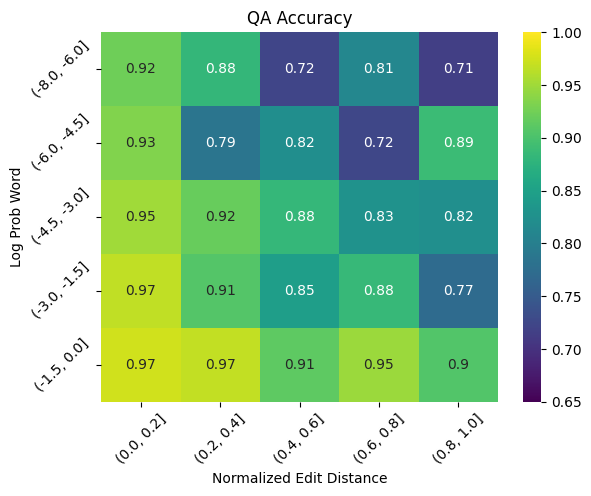

GPT recorded 88.8% accuracy, with accuracy decreasing with respect to normalized edit distance and increasing with respect to log word probability. This value alone doesn’t mean much, but the plots below do.

Predictably, increased typo complexity and decreased contextual information independently decrease accuracy. There are pretty precipitous drops at both the -7 log prob and 0.9 normalized edit distance thresholds, but the sample sizes are too small to make anything of it.

2. Ask for spellcheck

While we can’t tell what GPT is doing when given text with typos, it seems more likely that GPT is building feature representations on top of typos, rather than resolving typos before building features representations. If this is the case, a better approach might be to try resolving the typos before answering the question. That is, instead of letting GPT passively process typos, ask it to do active typo correction.

To do this, we introduce a five-shot spellcheck prompt. Here is one of the in-context examples:

User:

The following question may or may not contain spelling mistakes. Please respond with the corrected question.

Question: Where does my boyd go after I am no longer living?

Assistant:

Where does my body go after I am no longer living?

We feed each question into the spellcheck prompt, which returns the corrected question, then we feed the corrected question to the question answering prompt, and capture results.

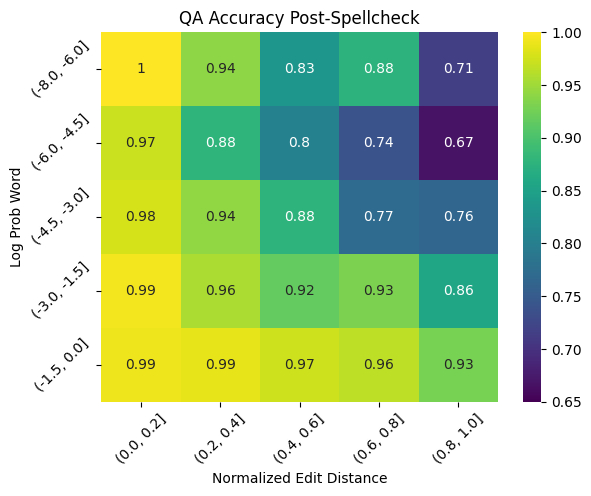

The active typo correction approach returns 92.0% accuracy, compared to 88.8% accuracy in the original approach. While the improvement is not large in absolute terms, it constitutes a 28% reduction in error.

You can see in the heatmap that the increase in accuracy is particularly pronounced for the easier examples, where either there was high context or low typo complexity. But in more difficult examples (looking toward the top right of the heatmap), the improvement is less obvious, and in some cases, it looks like active typo correction actually hurts performance.

One explanation is that, in the original approach, as typos became more complex their information content was effectively zero. The model likely paid little attention to typos that looked like nonsense. But in the active correction approach, the model is forced to attempt a typo correction, even when one is very difficult. As a consequence, difficult typos are often corrected to the wrong word, which can change the meaning of the question. Rather than contributing zero information, miscorrected typos contribute adversarial information. A similar argument can be made for typos on unlikely words: In these cases, the model may be more likely to correct to an incorrect word that it considers more likely.

We get some insight for this by looking at two classes of typo correction:

- Good correction: The passive approach got the answer wrong, but the active approach got the answer right.

- Bad correction: The passive approach got the answer right, but the active approach got the answer wrong.

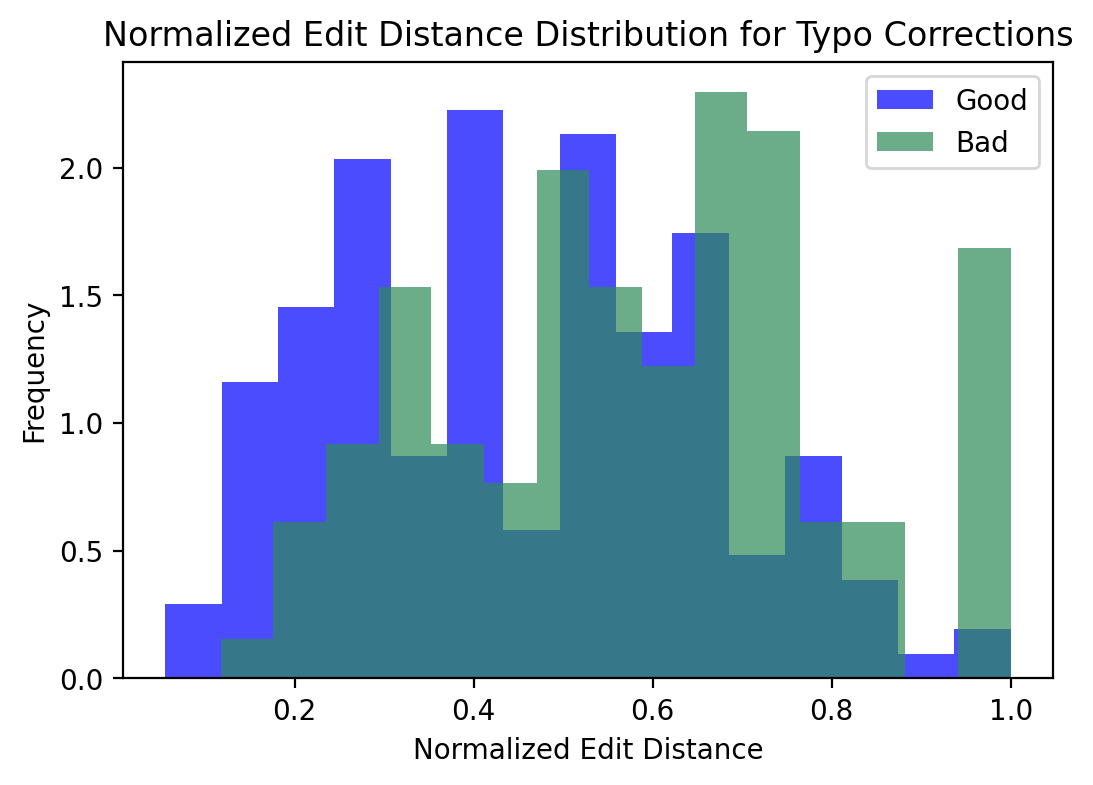

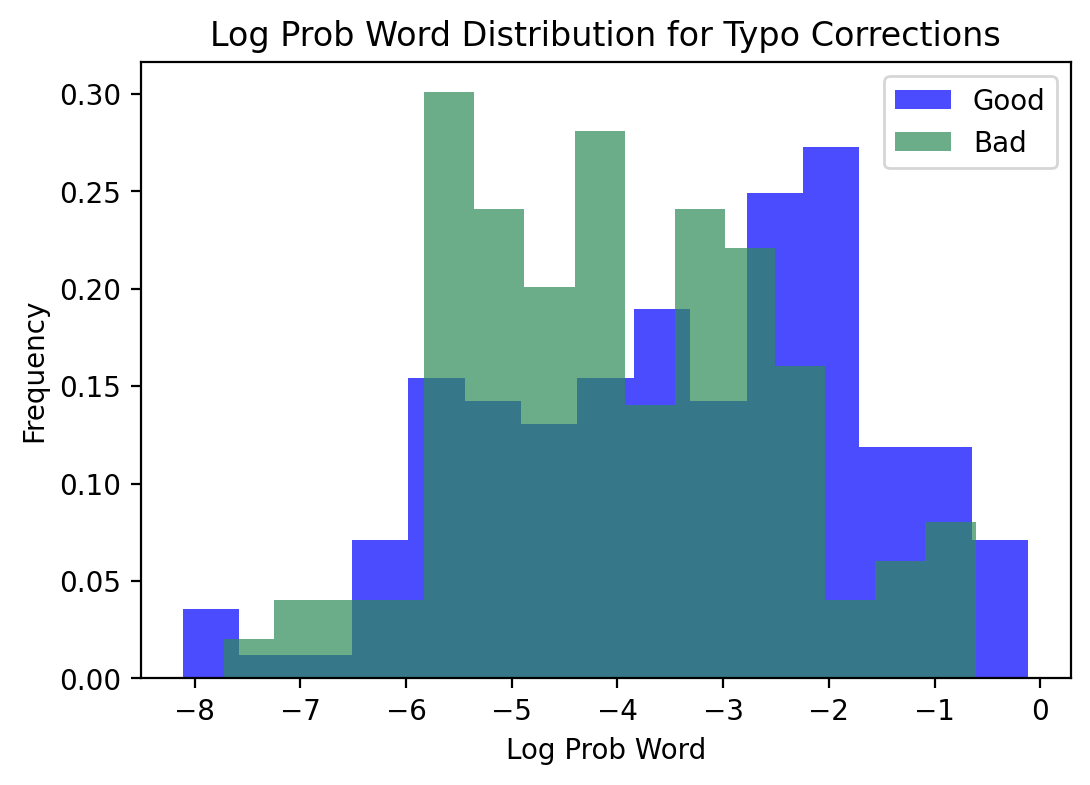

That is, while we expect the active correction approach to correct errors in the passive approach, sometimes it introduces errors where the passive approach was correct. The following figures show the distribution of good and bad typo corrections over normalized edit distance and log probability of target word.

The distributions confirm what we expected: As examples become more difficult, the model is more likely to suggest a correction that is incorrect and introduce an error where it otherwise would not. Active typo correction should be used with hesitation on text with very difficult typos. An optimized approach might involve correcting typos where the model is confident in the correction, and either returning the typoed word or an unknown token where the model finds the typo difficult.

There are two takeaways from these experiments:

- Typos hurt GPT question answering performance, and increasingly so as typos become more difficult (target word is hard to infer from text and typo complexity is high).

- Asking to fix typos before performing the question answering task yields better performance than performing the task on typoed text, but this approach may create adversarial examples when the typos are too difficult to resolve.

-

It also might be possible that these circuits do exist, but only for types of data/text that are input in a way such that characters are independently tokenized. Something similar was found for time series pattern recognition in TimeLLM: GPT struggled to detect patterns in numbers before the authors separated digits with spaces. Separating the digits made the model tokenize each digit individually, making it possible to recognize and continue patterns. A similar approach, which I don’t explore here, may be possible for typos: individually tokenize characters, and see if that enables the model to identify perturbation patterns. ↩

-

I say “may or may not contain …” here, because I also used this prompt on examples where the typo transformation did not change the word, and in these cases GPT would try to correct typos where there were none. I use “may or may not” instead of “may” because I found GPT was more likely to not correct non-typos when I added the “or may not” part. Ultimately, I threw out all examples where the typo transformation did not change the word, so this did not matter. Also worth noting that (1) all examples in the few-shot prompt contained typos and (2) sometimes the raw question contained typos itself (usually natural, small ones, for example “it’s” instead of “its”). ↩